As part of the ongoing trade battle between the two largest economies in the world, China has formally imposed tariffs on a wide range of American agricultural exports. China’s readiness to use food as a weapon against the US, which has long been one of its largest suppliers, highlights the government’s achievements in increasing agricultural self-sufficiency as well as the effect of a faltering economy on demand. Following early action on energy and essential metals, the agricultural tariffs range from 10% to 15% on a wide range of goods, including grains, proteins, cotton, and fresh vegetables. All American timber purchases and imports of soybeans from three US companies have also been suspended. Beijing also placed retaliatory duties on a variety of Canadian agricultural products on Saturday, which will take effect on March 20.

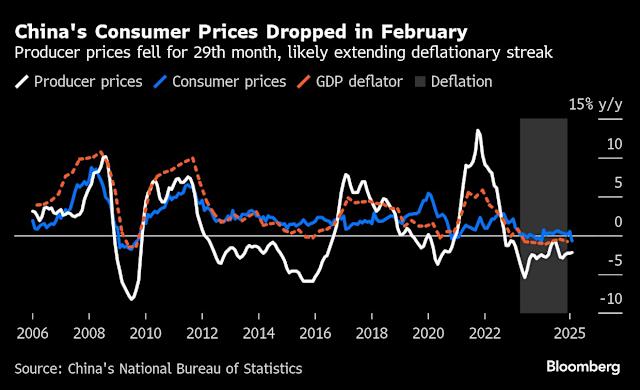

Providing enough food for the 1.4 billion people still tops the policy agenda. Even though China is still a major export destination for the Midwest farm belt’s mostly Republican states, Beijing’s attempts to reorganize supply chains during the trade battle during the first Trump administration have reduced Washington’s negotiating power. A bright spot in the Chinese economy’s dismal epidemic recovery has been the abundance of food. Addressing the effects of domestic excess has become increasingly urgent. Corn imports have fallen, while local wheat prices are at five-year lows. Sunday’s most recent data revealed that a sharp drop in food prices was driving deflation in consumer prices.

In response, the government has made an effort to safeguard its farmers. Soybean shipments have been delayed, and traders have been urged to restrict their foreign acquisitions of barley and sorghum. Beijing’s eagerness for trade probes and levies in recent months, which have targeted everything from seafood, meat, and dairy to rapeseed and pulses, indicates that policymakers aren’t too bothered by erecting obstacles to imports, especially when it comes to high-end goods that have been hardest hit by household budget cuts. All of these initiatives are supported by record grain production and a resolve to exploit this time of abundance to increase stockpiles. There is ongoing concern about livestock herds’ susceptibility to imported soy supply, which is reflected in the promotion of more technological solutions like cutting back on soybean meal in animal feeds.

As the United States’ largest agricultural export to China, soybeans are valued at around $13 billion in 2024 and have been the subject of strong efforts in recent years to reduce the nation’s reliance on other, less hostile suppliers like Brazil. Due to the seasonality of global production, the South American country will continue to receive the majority of Chinese imports until at least the fourth quarter, meaning that the 10% duty on US beans is unlikely to change much in the upcoming months. Naturally, the government will want to boost the economy, and getting consumers to part with their cash will be a major part of that. Food costs could increase and attitudes toward imports could shift if the government were to successfully stimulate the economy. Calculations would also be impacted by the impact of climate change-induced extreme weather on crops. Meanwhile, Beijing is using one of the more effective, less expensive tools in its trade armory to target American agricultural products.